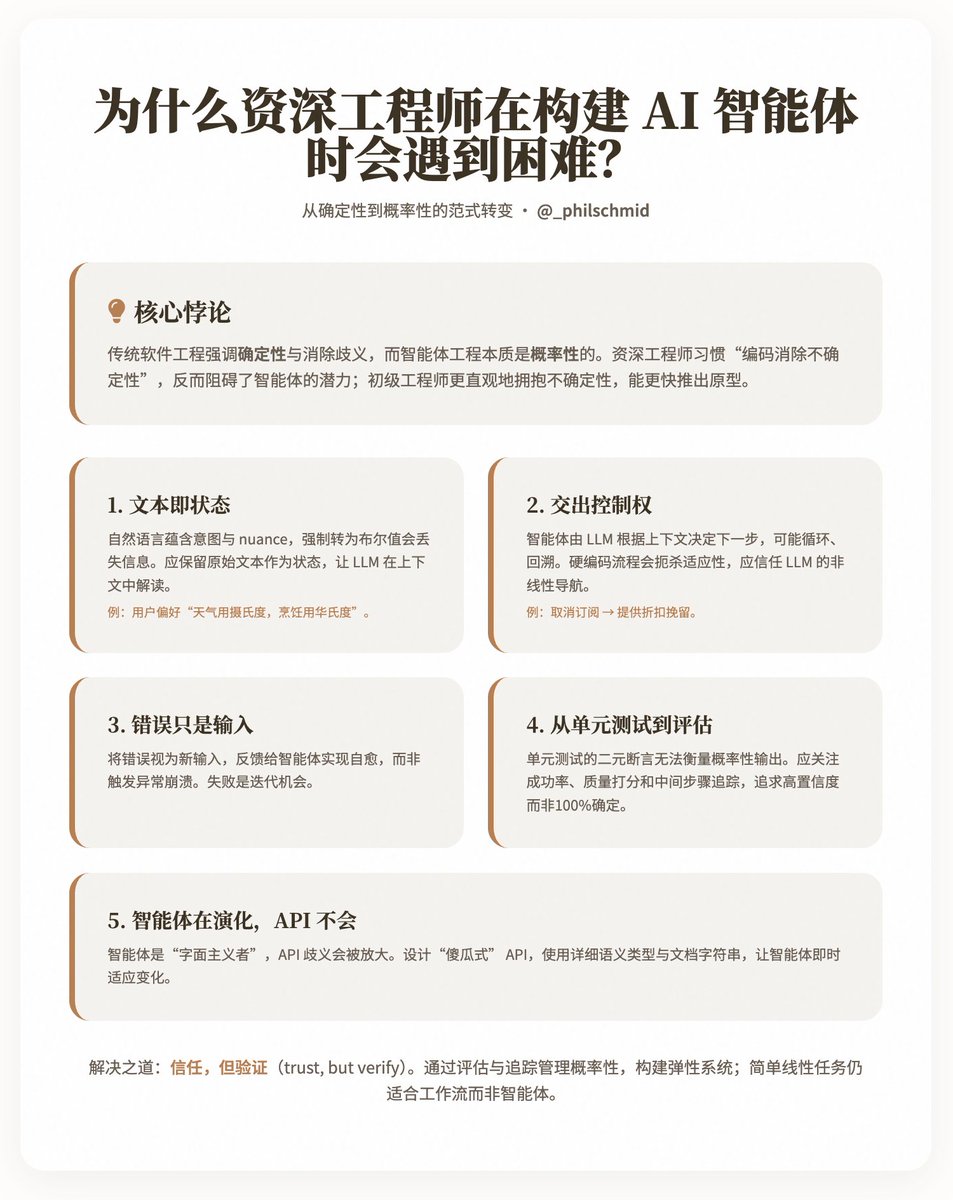

Why do senior engineers encounter difficulties when building AI agents? @philschmid shared an interesting paradox: why do experienced senior engineers often make slower and more difficult progress when developing AI agents compared to junior engineers? Schmid believes the root cause lies in the fact that traditional software engineering emphasizes determinism and disambiguation, while agent engineering is inherently probabilistic, requiring engineers to learn to "trust" LLMs (Local Level Models) to handle non-linear processes and natural language input. He analyzes the difficulties of this mindset shift through five key challenges and provides practical insights to help engineers adapt to this paradigm. Key Takeaways: A Paradigm Shift from Determinism to Probabilism. Traditional software development prioritizes predictability: fixed inputs, deterministic outputs, and error isolation through exception handling. In contrast, intelligent agents rely on LLMs as their "brain," driving decisions through natural language and allowing for multi-turn interactions, branching, and adaptation. However, senior engineers' instinct is to "code away uncertainty," which ironically hinders the potential of intelligent agents. Schmid points out that junior engineers tend to embrace uncertainty more intuitively and can produce working prototypes faster, while senior engineers need to overcome habits developed over many years. The five core challenges outline five points of conflict between traditional engineering practices and agent development. Each challenge is accompanied by explanations and examples, highlighting how to shift to a more flexible approach. 1. Text is the New State Traditional systems use structured data (such as Boolean values like `is_approved: true/false`) to represent states, ensuring discreteness and predictability. However, real-world intentions are often hidden in the nuances of natural language, such as the user feedback "This plan looks good, but please focus on the US market." Forcing a binary structure into a system would lose these nuances, preventing the agent from responding dynamically. Insight: Preserve the original text as state, allowing LLMs to interpret it within context. For example, store user preferences such as "I prefer Celsius for weather, but use Fahrenheit for cooking" instead of simple Boolean values. This requires engineers to shift from "structure-first" to "semantic flexibility." 2. Handing over control Traditional architectures like microservices rely on fixed routes and API endpoints to control processes. However, an agent has only a single natural language entry point, with the LLM determining the next step based on tools and context—potentially looping, backtracking, or redirecting. For example, an "unsubscribe" intent might be negotiated to "offer a discount to retain the agent." Hardcoding these processes stifles the agent's adaptability. Insight: Trust the LLM to handle control flow and leverage its understanding of the full context. Engineers should design systems that support this "non-linear navigation," rather than pre-setting all branches. 3. Errors are just inputs. In traditional code, errors (such as missing variables) trigger exceptions, leading to crashes or retries. However, each execution of an agent consumes time and resources, making complete failure unacceptable. The authors emphasize that errors should be treated as new input, fed back to the agent to enable self-healing. Insight: Build a resilient mechanism that loops errors back into the LLM for recovery, rather than isolating them. This reflects probabilistic thinking: failure is not the end, but an opportunity for iteration. 4. From Unit Tests to Evals Unit tests rely on binary assertions (pass/fail), which are suitable for deterministic outputs. However, the output of an agent is probabilistic; for example, "summarize this email" may produce countless valid variations. Tests simulating LLMs also only verify implementation details, not overall behavior. Insight: Shift towards "evals," which include reliability (success rate, such as 45/50 passes), quality (using LLM as a judge to score helpfulness and accuracy), and tracking (checking intermediate steps, such as whether a knowledge base was consulted). The goal is not 100% certainty, but a high-confidence probability of success. 5. Agents evolve, APIs don't. APIs are designed on the assumption that human users can infer context, but intelligent agents are "literalists"—if "email" in get_user(id) is misinterpreted as a UUID, it might hallucinate an incorrect response. API ambiguity amplifies the limitations of LLMs. Insight: Design "foolproof" APIs using detailed semantic types (such as delete_item_by_uuid(uuid: str)) and docstrings. Intelligent agents can adapt to API changes instantly, making them more flexible than traditional code. Solutions and Implications Schmid does not advocate completely abandoning engineering principles, but rather seeks a balance of "trust, but verify": building resilient systems by evaluating and tracking probabilistic management. At the same time, he recognizes that agents are not omnipotent—simple linear tasks are better suited to workflows than agents. Examples include preserving the text state of user feedback, allowing error-driven recovery loops, and quantifying agent performance using evaluations (e.g., 90% success rate, 4.5/5 quality score). Blog address:

Loading thread detail

Fetching the original tweets from X for a clean reading view.

Hang tight—this usually only takes a few seconds.